Metagenome Assembly

Overview

Teaching: 40 min

Exercises: 40 minQuestions

Why do raw reads need to be assembled?

How does metagenomic assembly differ from genomic assembly?

How can we assemble a metagenome?

Objectives

Run a metagenomic assembly workflow.

Assess the quality of an assembly using SeqKit

IMPORTANT

The analyses in this lesson will take several hours to complete! You can find some recommended reading at the end of the page that you might want to read whilst you’re waiting.

Assembling reads

In the last episode, we put both the long and short raw reads through quality control. They are now ready to be assembled into a metagenome. Genomic assembly is the process of joining smaller fragments of DNA (i.e., reads) to make longer segments to try and reconstruct the original genomes.

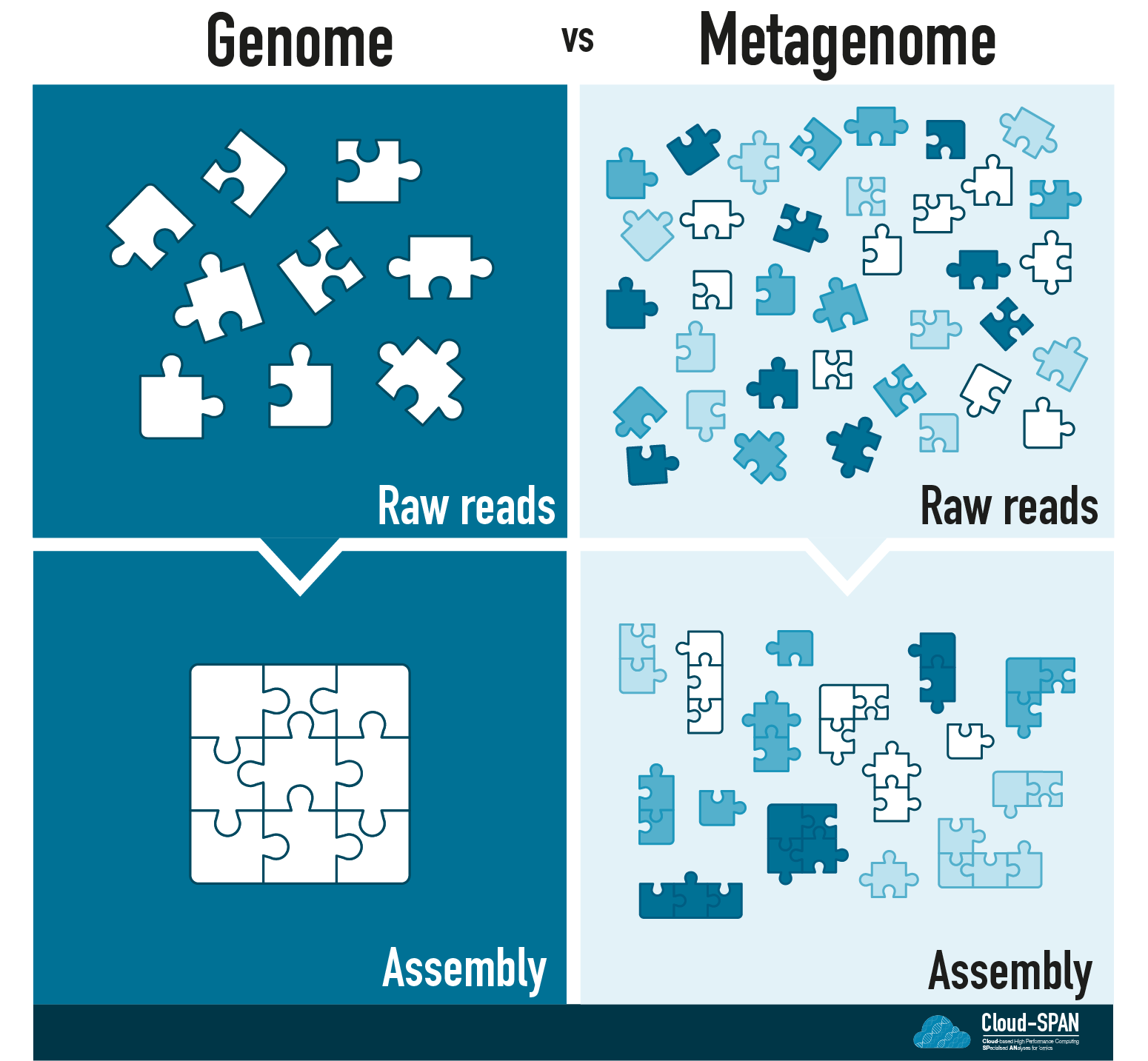

Genomic assembly

You can think of Genomic assembly as a jigsaw puzzle: each raw read corresponds to a piece of the puzzle and you are aiming to complete the puzzle by joining these pieces together in the right order.

There are two main strategies for genome assembly:

- Mapping to a reference genome - requires that there is a complete genome of the organism you have sequenced, or a closely related organism. This is the approach you would take if you were trying to identify variants for well-characterised species, such as humans.

- De novo assembly - does not use a reference but instead assembles reads together based on the content of the reads (the specific approach depends on which assembly software you are using). It is commonly used for environmental samples which usually contain many organisms that have not been cultured previously.

Continuing the jigsaw analogy, mapping to a reference genome would be equivalent to having an image of the final puzzle to compare your assembly to. In contrast, in de novo assembly you would have to depend entirely on which pieces fit together.

Metagenomic assembly

Metagenomic sequencing adds another layer to the challenge of assembly! Instead of having one organism to assemble you now have many! Depending on the complexity of a metagenome you could have anywhere from a handful of organisms in a community to thousands.

You no longer have one jigsaw puzzle, but many with all the pieces mixed together.

Many of the communities sequenced using metagenomics contain previously uncultured microbes (often known as microbial dark matter) so they are unlikely to have reference genomes. In addition, you don’t usually know what you are sequencing - the community of organisms is unknown.

Assembling our metaphorical jigsaw will be a challenge. We have many, perhaps thousands, of jigsaws to assemble and no pictures

Luckily there are programs, known as assemblers, that will do this for us!

Metagenomic assembly faces additional problems, which means we need an assembler built to handle metagenomes. These additional problems include:

- Differences in coverage between the genomes, due to differences in abundance across the sample.

- The fact that different species often share conserved regions.

- The presence of several strains of a single species in the community

The assembly strategy also differs based on the sequencing technology used to generate the raw reads. Here we’re using raw data from Nanopore sequencing as the basis for this metagenome assembly so we need to use a metagenome assembler appropriate for long-read sequencing.

We will be using Flye, which is a long-read de novo assembler for assembling large and complex data with a metagenomic mode. Like all our programs, Flye has been pre-installed onto your instance.

Flye is a long-read assembler

Important

Make sure you’re still logged into your cloud instance. If you can’t remember how to log on, visit the instructions from earlier today.

Navigate to the analysis directory you made in a previous step.

cd ~

cd cs_course/analysis

Run the flye command without any arguments to see a short description of its use:

flye

$ flye

usage: flye (--pacbio-raw | --pacbio-corr | --pacbio-hifi | --nano-raw |

--nano-corr | --nano-hq ) file1 [file_2 ...]

--out-dir PATH

[--genome-size SIZE] [--threads int] [--iterations int]

[--meta] [--polish-target] [--min-overlap SIZE]

[--keep-haplotypes] [--debug] [--version] [--help]

[--scaffold] [--resume] [--resume-from] [--stop-after]

[--read-error float] [--extra-params]

flye: error: the following arguments are required: -o/--out-dir

A full description can be displayed by using the --help flag:

flye --help

flyehelp documentationusage: flye (--pacbio-raw | --pacbio-corr | --pacbio-hifi | --nano-raw | --nano-corr | --nano-hq ) file1 [file_2 ...] --out-dir PATH [--genome-size SIZE] [--threads int] [--iterations int] [--meta] [--polish-target] [--min-overlap SIZE] [--keep-haplotypes] [--debug] [--version] [--help] [--scaffold] [--resume] [--resume-from] [--stop-after] [--read-error float] [--extra-params] Assembly of long reads with repeat graphs optional arguments: -h, --help show this help message and exit --pacbio-raw path [path ...] PacBio regular CLR reads (<20% error) --pacbio-corr path [path ...] PacBio reads that were corrected with other methods (<3% error) --pacbio-hifi path [path ...] PacBio HiFi reads (<1% error) --nano-raw path [path ...] ONT regular reads, pre-Guppy5 (<20% error) --nano-corr path [path ...] ONT reads that were corrected with other methods (<3% error) --nano-hq path [path ...] ONT high-quality reads: Guppy5+ or Q20 (<5% error) --subassemblies path [path ...] [deprecated] high-quality contigs input -g size, --genome-size size estimated genome size (for example, 5m or 2.6g) -o path, --out-dir path Output directory -t int, --threads int number of parallel threads [1] -i int, --iterations int number of polishing iterations [1] -m int, --min-overlap int minimum overlap between reads [auto] --asm-coverage int reduced coverage for initial disjointig assembly [not set] --hifi-error float [deprecated] same as --read-error --read-error float adjust parameters for given read error rate (as fraction e.g. 0.03) --extra-params extra_params extra configuration parameters list (comma-separated) --plasmids unused (retained for backward compatibility) --meta metagenome / uneven coverage mode --keep-haplotypes do not collapse alternative haplotypes --scaffold enable scaffolding using graph [disabled by default] --trestle [deprecated] enable Trestle [disabled by default] --polish-target path run polisher on the target sequence --resume resume from the last completed stage --resume-from stage_name resume from a custom stage --stop-after stage_name stop after the specified stage completed --debug enable debug output -v, --version show program's version number and exit Input reads can be in FASTA or FASTQ format, uncompressed or compressed with gz. Currently, PacBio (CLR, HiFi, corrected) and ONT reads (regular, HQ, corrected) are supported. Expected error rates are <15% for PB CLR/regular ONT; <5% for ONT HQ, <3% for corrected, and <1% for HiFi. Note that Flye was primarily developed to run on uncorrected reads. You may specify multiple files with reads (separated by spaces). Mixing different read types is not yet supported. The --meta option enables the mode for metagenome/uneven coverage assembly. To reduce memory consumption for large genome assemblies, you can use a subset of the longest reads for initial disjointig assembly by specifying --asm-coverage and --genome-size options. Typically, 40x coverage is enough to produce good disjointigs. You can run Flye polisher as a standalone tool using --polish-target option.

Flye has multiple different options available and we need to work out which ones are appropriate for our dataset.

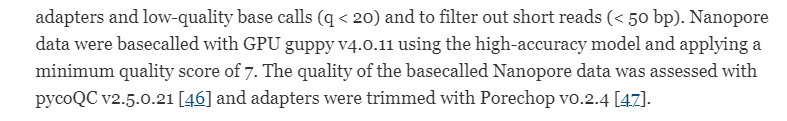

The most important thing to know is which program was used to basecall our reads, as this determines which of (--pacbio-raw | --pacbio-corr | --pacbio-hifi | --nano-raw | --nano-corr | --nano-hq ) we choose. In the Methods section of our source paper the authors state that:

This means we should use the --nano-raw option, as the reads were called with a version of Guppy that precedes v5 (Guppy is a program used to convert the signals that come out of a sequencer into an actual string of bases). This option will be followed by the relative path to the long-read .fastq file.

We also need to choose how many times we want Flye to ‘polish’ the data after assembly. Polishing is a way to improve the accuracy of the assembly. The number of rounds of polishing is specified using -i or --iterations. We will do three rounds of polishing, which is a standard practice (though the default in Flye is one round only).

The other options are a bit easier:

- We use

-oor--outdirto specify (using a relative path) where the Flye output should be stored - We also use the

-tor--threadsflag in order to run the assembly on multiple threads (aka running several processes at once) in order to speed it up - Finally we indicate that the dataset is a metagenome using the

--metaoption

Unused parameters

There are many parameters that we don’t need. Some of these are deprecated and some are only appropriate for certain types of data. Others are useful to allow tweaking to try to further improve an assembly (e.g.

--genome-sizeand--read-error).Most bioinformatics programs have an associated website (which is often a GitHub page) with a whole manual to use the program. The Flye Manual contains a lot of further information about the parameters available. If you’re going to try using Flye on your own long-read dataset this is a good place to start.

Now we’ve worked out what parameters are appropriate for our data we can put them all together in one command. Since the command is quite long, we will use backward slashes to allow it to span several lines. \ basically means “start a new line and carry on reading without submitting the command”.

First let’s make sure we’re in the analysis directory, and make a new directory called assembly for the Flye output.

cd ~/cs_course/analysis/

mkdir assembly

Now we can start constructing our command! You can type/copy this code into your command line but don’t press enter just yet.

flye --nano-raw ~/cs_course/data/nano_fastq/ERR5000342_sub12_filtered.fastq \

--out-dir assembly \

--threads 8 \

--iterations 3 \

--meta

--nano-rawtells Flye that it is receiving pre-Guppy5 reads and that the input is found at the path~/cs_course/data/nano_fastq/ERR5000342_sub12_filtered.fastq(note that we are using our ‘filtered reads’ - there’d be no point doing quality control and filtering otherwise!)--out-dirtells Flye that the output should be saved in theassembly/directory--threadsindicates that the number of parallel cores is8--iterationsindicates that the data will be polished3times--metaindicates that the dataset is a metagenome

Don’t run this command yet! If you have, you can press Ctrl+z to stop the command.

Now we’ve built our command we could stop here but metagenomic assembly takes a long time. If we were to run this command as is we’d have to stay logged into the instance (aka leaving your computer running) for hours.

Luckily we don’t have to do that as we’re using a remote computer.

Running a command in the background

All the commands we have run so far have been in the “foreground”, meaning they’ve been run directly in the terminal window, the prompt disappears and we can’t use the terminal again until the command is finished.

Commands can also be run in the “background” so the prompt is returned before the command is finished and we can continue using our terminal. Commands run in the background are often called “jobs”. A major advantage of running a long job in the background is that you can log out of your instance without killing the process.

Warning

If you run the job in the foreground it will stop as soon as you log out of the instance! Running jobs in the background is your friend!

To run a command in the background, we follow it with an ampersand (&) symbol.

The final thing to add to our flye command is “redirection”: &> flye_output.txt will send any output that would be sent to the terminal to a file, flye_output.txt instead

The complete command is:

flye --nano-raw ~/cs_course/data/nano_fastq/ERR5000342_sub12_filtered.fastq \

--out-dir assembly \

--threads 8 \

--iterations 3 \

--meta &> flye_output.txt &

&> redirects sends information that would normally go to the terminal to a file instead. This means any logging and progress information flye creates will be saved in flye_output.txt. Note the lack of a space between &>. The second & then runs this command in the background.

We can now press enter to run the command. Your prompt should immediately return. This doesn’t mean that the code has finished already: it is now running in the background.

Running commands on different servers

There are many different ways to run jobs in the background in a terminal.

How you run these commands will depend on the computing resources (and their fair use policies) you are using The main options include:

&, which we’ve covered here. Depending on the infrastructure you’re running the command on, you may also need to usenohupto prevent the background job from being killed when you close the terminal.- The command line program

screen, which allows you to create a shell session that can be completely detached from a terminal and re-attached when needed.- Queuing system - many shared computing resources, like the High Performance Computing (HPC) clusters owned by some Universities, operate a queuing system (e.g. SLURM or SGE) so each user gets their fair share of computing resources. With these you submit your command / job to the queueing system, which will then handle when to run the job on the resources available.

As we’re running the command in the background we no longer see the output on the terminal but we can still check on the progress of the assembly. There are two options to do this.

- Using the command

jobsto view what is running - Examining the log file created by

flyeusingless

Checking progress: jobs

Jobs command is used to list the jobs that you are running in the background and in the foreground. If the prompt is returned with no information no commands are being run.

jobs

[1]+ Running flye --nano-raw ~/cs_course/data/nano_fastq/ERR5000342_sub12_filtered.fastq --out-dir assembly --threads 8 --iterations 3 --meta &> flye_output.txt &

The [1] is the job number. If you need to stop the job running, you can use kill %1, where 1 is the job number.

Checking progress: the log file

Flye generates a log file when running, which is stored in the output folder it has generated.

Using less we can navigate through this file.

less assembly/flye.log

The contents of the file will depend on how far through the assembly Flye is. At the start of an assembly you’ll probably see something like this:

[2022-10-05 17:22:03] INFO: Starting Flye 2.9.1-b1780

[2022-10-05 17:22:03] INFO: >>>STAGE: configure

[2022-10-05 17:22:03] INFO: Configuring run

[2022-10-05 17:22:17] INFO: Total read length: 3023658929

[2022-10-05 17:22:17] INFO: Reads N50/N90: 5389 / 2607

[2022-10-05 17:22:17] INFO: Minimum overlap set to 3000

[2022-10-05 17:22:17] INFO: >>>STAGE: assembly

Different steps in the assembly process take different amounts of time so it might appear stuck. However, it is almost certainly still running if it was run in the background.

Note: this log file will contain data similar to the data in the flye_output.txt file we’re generating when redirecting the terminal output. But it’s easier to look at the log file as flye will always generate that even if you’re running the command differently (e.g. in the foreground).

Navigation commands in

less:

key action Space to go forward b to go backward g to go to the beginning G to go to the end q to quit See Prenomics - Working with Files and Directories for a full overview on using

less.

Flye is likely to take up to 5 hours to finish assembling - so feel free to leave this running overnight and come back to it tomorrow. You don’t need to remain connected to the instance during this time (and you can turn your computer off!) but once you have disconnected from the instance it does mean you can no longer use jobs to track the job.

In the meantime, if you wanted to read more about assembly and metagenomics there’s a few papers and resources at the end with recommended reading.

Determining if the assembly has finished

After leaving it several hours, Flye should have finished assembling.

If you remained connected to the instance during the process you will be able to tell it has finished because you get the following output in your terminal when the command has finished.

[2]+ Done flye --nano-raw ~/cs_course/data/nano_fastq/ERR5000342_sub12_filtered.fastq --out-dir assembly --threads 8 --iterations 3 --meta &> flye_output.txt &

This message won’t be displayed if you disconnected from the instance for whatever reason during the assembly process. However, you can still examine the flye.log file in the assembly directory. If the assembly has finished the log file will have summary statistics and information about the location of the assembly at the end.

Move to the assembly directory and use less to examine the contents of the log file:

cd ~/cs_course/analysis/assembly/

less flye.log

Navigate to the end of the file using G. You should see something like:

[2023-02-24 14:41:27] root: INFO: Assembly statistics:

Total length: 18872828

Fragments: 1161

Fragments N50: 20921

Largest frg: 118427

Scaffolds: 0

Mean coverage: 7

[2023-02-24 14:41:27] root: INFO: Final assembly: /home/csuser/cs_course/analysis/assembly/assembly.fasta

There are some basic statistics about the final assembly created.

What is the Assembly output?

If we use ls in the assembly directory we can see the that Flye has created many different files.

00-assembly 20-repeat 40-polishing assembly_graph.gfa assembly_info.txt params.json

10-consensus 30-contigger assembly.fasta assembly_graph.gv flye.log

One of these is flye.log which we have already looked at.

- Flye generates a directory to contain the output for each step of the assembly process. (These are the

00-assembly,10-consensus,20-repeat,30-contiggerand40-polishingdirectories.) - We also have a file containing the parameters we ran the assembly under

params.jsonwhich is useful to keep our analysis reproducible. - The assembled contigs are in FASTA format (

assembly.fasta), a common standard file type for storing sequence data without its quality scores. - There’s a text file which contains more information about each contig created (

assembly_info.txt). - Finally we have two files for a repeat graph (

assembly_graph.gfaorassembly_graph.gv) which is a visual way to view the assembly.

You can see more about the output for Flye in the documentation on GitHub.

Contigs vs. reads

We have seen reads in the raw sequencing data - these are our individual jigsaw pieces.

Contigs (from the word contiguous) are longer fragments of DNA produced after raw reads are joined together by the assembly process. These are like the chunks of the jigsaw puzzle the assembler has managed to complete. Contigs are usually much longer than raw reads but vary in length and number depending on how successful the assembly has been.

Assembly Statistics

Flye gave us basic statistics about the size of the assembly but not all assemblers do. We can use Seqkit to calculate summary statistics from the assembly. We previously used another Seqkit command, seq to Filter our Nanopore sequences by quality. This time we will use the command stats.

Make sure you are in the assembly folder then run seqkit stats on assembly.fasta:

cd ~/cs_course/analysis/assembly/

seqkit stats assembly.fasta

SeqKit is fast so we have run the command in the terminal foreground. It should take just a couple of seconds to process this assembly. Assemblies with more sequencing data can take a bit longer.

Once it has finished you should see an output table like this:

file format type num_seqs sum_len min_len avg_len max_len

assembly.fasta FASTA DNA 790 11,957,486 511 15,136.1 95,862

This table shows the input file, the format of the file, the type of sequence and other statistics. The assembly process introduces small random variations in the assemly so your table will likely differ slightly. However, you should expect the numbers to be very similar.

Using this table of statistics, answer the questions below.

Exercise 1: Looking at basic statistics

Using the output for seqkit stats above, answer the following questions.

a) How many contigs are in this assembly?

b) How many bases in total have been assembled?

c) What is the shortest and longest contig produced by this assembly?Solution

From our table:

a) Fromnum_seqswe can see that this assembly is made up of 790 contigs

b) Looking atsum_lengthwe can see that the assembly is 11,957,486bp in total (over 11 million bp!)

c) Frommin_lengthwe can see the shortest contig is 511p and frommax_lengththe longest contig is 95,862bp

Recommended reading:

While you’re waiting for the assembly to finish here are some things you might want to read about:

- An overall background to the history of DNA sequencing in DNA sequencing at 40: past, present and future

- An overview of a metagenomics project Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis - though note this paper is from 2017 so some techniques and software will be different now.

- The challenges of genomic and metagenomic assembly and the algorithms that have been built to overcome these in Assembly Algorithms for Next-Generation Sequencing Data

- The approach Flye uses to assemble metagenomes is covered in metaFlye: scalable long-read metagenome assembly using repeat graphs

- Comparison of genome assembly for bacteria Comparison of De Novo Assembly Strategies for Bacterial Genomes

- Benchmarking of assemblers including flye in prokaryotes Benchmarking of long-read assemblers for prokaryote whole genome sequencing

- Comparison of combined assembly and polishing method Trycycler: consensus long-read assemblies for bacterial genomes

- Using nanopore to produce ultra long reads and contiguous assemblies Nanopore sequencing and assembly of a human genome with ultra-long reads

Key Points

Assembly merges raw reads into contigs.

Flye can be used as a metagenomic assembler.

Certain statistics can be used to describe the quality of an assembly.