Functional annotation

What is functional annotation?

Now we have our binned MAGs, we can start to think about what functions genes contained within their genomes do. We can do this via functional annotation - a way to collect information about and describe a DNA sequence.

Next lesson we will talk about taxonomic annotation, which tells us which organisms are present in the metagenome assembly. This lesson, however, we will do some brief functional annotation to get more information about the potential metabolic capacity of the organism we are annotating. This is possible because there is software available which uses features in DNA sequences to predict where genes start and end, allowing us to predict which genes are in our MAGs.

A high quality functional annotation is important because it is very useful for lots of downstream analyses. For instance, if we were looking for genes that have a particular function, we would only be able to do that if we were able to predict the location of the genes in these assemblies.

For example, the paper this data is pulled from uses functional annotation of MAGs to look for genes associated with denitrification pathways. The abundance of these genes is then linked to N2O flux rates at different sites.

In this lesson we will only be doing a very small amount of functional annotation using the tool Prokka for rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. This is intended as a taster to give you an idea what you can use your MAGs for. There are many other routes to be taken regarding functional annotation, some of which will be discussed briefly at the end of this episode.

As with taxonomic annotation, effectiveness is determined by the database that the MAG sequence is being compared to. If you do not use the appropriate database you may not end up with many annotated sequences. In particular, Prokka (the tool we will use in this episode) annotates archaea and bacterial genomes. If you are trying to annotate a fungal genome or a eukaryote, you will need to use something different.

Using Prokka for functional annotation

We are using Prokka here as it is still the software most commonly used. However, the program is no longer being updated. One recent alternative that is being actively developed is Bakta.

Prokka identifies candidate genes in a iterative process. First it uses Prodigal (another command line tool) to find candidate genes.These are then compared against databases of known protein sequences in order to determine their function. If you like, you can read more about Prokka in this 2014 paper.

Prokka has been pre-installed on our instance. First, let’s create a directory inside results where we can store our outputs from Prokka.

Code

cd ~/cs_course

mkdir results/prokkaFor now we will annotate just one MAG at a time with Prokka. In the previous episode we produced 90 MAGs of varying quality. In this example, we will start with the MAG bin.45.fa, as this MAG had fairly high completeness (57.76%) and only 1.72% contamination. You should choose your own “best” bin to use (one with good completeness and low contamination).

Before we start we’ll need to activate a conda environment to run the software.

Activating an environment

Environments are a way of installing a piece of software so that it is isolated, so that things installed within an environment, do not affect other software installed at system wide level. For some pieces of software, the requirements for different dependency versions, such different versions of python mean this is an easy way to have multiple pieces of software installed without conflicts. One popular way to manage environments is to use conda which is a popular environment manager. We will not discuss using conda in detail, so for further information of how to use it, here is a Carpentries course that covers how to use conda in more detail.

For this course we have created a conda environment containing prokka. In order to use this we will need to use the conda activate command:

Code

conda activate prokkaYou will be able to tell you have activated your environment because your prompt should go from looking like this, with (base) at the beginning…

Code

(base) csuser@instance001:~ $…to having (prokka) at the beginning. If you forget whether you are in an the prokka environment, look back to see what the prompt looks like.

Code

(prokka) csuser@instance001:~ $Now let’s take a look at the help page for Prokka using the -h flag.

Code

prokka -hName:

Prokka 1.12 by Torsten Seemann <torsten.seemann@gmail.com>

Synopsis:

rapid bacterial genome annotation

Usage:

prokka [options] <contigs.fasta>General:

--help This help

--version Print version and exit

--docs Show full manual/documentation

--citation Print citation for referencing Prokka

--quiet No screen output (default OFF)

--debug Debug mode: keep all temporary files (default OFF)

Setup:

--listdb List all configured databases

--setupdb Index all installed databases

--cleandb Remove all database indices

--depends List all software dependencies

Outputs:

--outdir [X] Output folder [auto] (default '')

--force Force overwriting existing output folder (default OFF)

--prefix [X] Filename output prefix [auto] (default '')

--addgenes Add 'gene' features for each 'CDS' feature (default OFF)

--addmrna Add 'mRNA' features for each 'CDS' feature (default OFF)

--locustag [X] Locus tag prefix [auto] (default '')

--increment [N] Locus tag counter increment (default '1')

--gffver [N] GFF version (default '3')

--compliant Force Genbank/ENA/DDJB compliance: --addgenes --mincontiglen 200 --centre XXX (default OFF)

--centre [X] Sequencing centre ID. (default '')

--accver [N] Version to put in Genbank file (default '1')

Organism details:

--genus [X] Genus name (default 'Genus')

--species [X] Species name (default 'species')

--strain [X] Strain name (default 'strain')

--plasmid [X] Plasmid name or identifier (default '')

Annotations:

--kingdom [X] Annotation mode: Archaea|Bacteria|Mitochondria|Viruses (default 'Bacteria')

--gcode [N] Genetic code / Translation table (set if --kingdom is set) (default '0')

--gram [X] Gram: -/neg +/pos (default '')

--usegenus Use genus-specific BLAST databases (needs --genus) (default OFF)

--proteins [X] FASTA or GBK file to use as 1st priority (default '')

--hmms [X] Trusted HMM to first annotate from (default '')

--metagenome Improve gene predictions for highly fragmented genomes (default OFF)

--rawproduct Do not clean up /product annotation (default OFF)

--cdsrnaolap Allow [tr]RNA to overlap CDS (default OFF)

Computation:

--cpus [N] Number of CPUs to use [0=all] (default '8')

--fast Fast mode - only use basic BLASTP databases (default OFF)

--noanno For CDS just set /product="unannotated protein" (default OFF)

--mincontiglen [N] Minimum contig size [NCBI needs 200] (default '1')

--evalue [n.n] Similarity e-value cut-off (default '1e-06')

--rfam Enable searching for ncRNAs with Infernal+Rfam (SLOW!) (default '0')

--norrna Don't run rRNA search (default OFF)

--notrna Don't run tRNA search (default OFF)

--rnammer Prefer RNAmmer over Barrnap for rRNA prediction (default OFF)Looking at the help page tells us how to construct our basic command, which has these arguments: - --outdir tells Prokka where to put the output - --prefix tells Prokka what to call the outputs (in this case, the name of the bin will suffice) - finally we need to provide the file to be annotated

Prokka produces multiple different file types, which you can see in the table below. We are mainly interested in .faa, .ffn and .tsv but many of the other files are useful for submission to different databases.

| Suffix | Description of file contents |

|---|---|

| .fna | FASTA file of original input contigs (nucleotide) |

| .faa | FASTA file of translated coding genes (protein) |

| .ffn | FASTA file of all genomic features (nucleotide) |

| .fsa | Contig sequences for submission (nucleotide) |

| .tbl | Feature table for submission |

| .sqn | Sequin editable file for submission |

| .gbk | Genbank file containing sequences and annotations |

| .gff | GFF v3 file containing sequences and annotations |

| .log | Log file of Prokka processing output |

| .txt | Annotation summary statistics |

| .tsv | Tab-separated file of all features: locus_tag,ftype,len_bp,gene,EC_number,COG,product |

Code

prokka --outdir results/prokka/bin.45 --prefix bin.45 results/binning/assembly_ERR5000342.fasta.metabat-bins1500-YYYMMDD_HHMMSS/bin.45.faThis should take around 1-2 minutes on the instance so we will not be running the command in the background.

Test yourself! What do each of these parts of the command signal?

--outdir bin.45--prefix bin.45results/binning/assembly_ERR5000342.fasta.metabat-bins1500-YYYMMDD_HHMMSS/bin.45.fa

bin.45is the name of the directory where Prokka will place its output filesbin.45will be the name of each output file e.g.bin.45.tsvorbin.45.faa- This is the file path for the file we want Prokka to annotate

When you initially run the command you should see similar to the following.

Output

[11:58:55] This is prokka 1.12

[11:58:55] Written by Torsten Seemann <torsten.seemann@gmail.com>

[11:58:55] Homepage is https://github.com/tseemann/prokka

[11:58:55] Local time is Wed Mar 22 11:58:55 2023

[11:58:55] You are csuser

[11:58:55] Operating system is linux

[11:58:55] You have BioPerl 1.006924

[11:58:55] System has 8 cores.

[11:58:55] Will use maximum of 8 cores.

[11:58:55] Annotating as >>> Bacteria <<<

[11:58:55] Generating locus_tag from 'results/binning/assembly_ERR5000342.fasta.metabat-bins1500-YYYMMDD_HHMMSS/bin.45.fa' contents.And you should see the following when the command has finished:

Output

[12:00:28] Output files:

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.fna

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.faa

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.ffn

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.fsa

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.err

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.sqn

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.txt

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.gbk

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.tsv

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.gff

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.log

[12:00:28] bin.45/bin.45.tbl

[12:00:28] Annotation finished successfully.

[12:00:28] Walltime used: 1.55 minutes

[12:00:28] If you use this result please cite the Prokka paper:

[12:00:28] Seemann T (2014) Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 30(14):2068-9.

[12:00:28] Type 'prokka --citation' for more details.

[12:00:28] Share and enjoy!Now prokka has finished running, we can exit the conda environment using the conda deactivate command.

Code

conda deactivateYour prompt should return from something like this:

Code

(prokka) csuser@metagenomicsT3instance04:~ $ conda deactivateto this:

Code

(base) csuser@metagenomicsT3instance04:~ $If we navigate into the bin.45 output file we can use ls to see that Prokka has generated many files.

Code

cd results/prokka/bin.45

lsOutput

bin.45.err bin.45.faa bin.45.ffn bin.45.fna bin.45.fsa bin.45.gbk bin.45.gff bin.45.log bin.45.sqn bin.45.tbl bin.45.tsv bin.45.txtAs mentioned previously, the two files we are most interested in are those with the extension .tsv and .faa:

- the

.tsvfile contains information about every gene identified by Prokka - the

.faafile is a FASTA file containing the amino acid sequence of every gene that has been identified.

We can take a look at the .tsv file using head.

Code

head bin.45.tsvOutput

locus_tag ftype gene EC_number product

DDJNKIGN_00001 CDS hypothetical protein

DDJNKIGN_00002 CDS hypothetical protein

DDJNKIGN_00003 CDS macA Macrolide export protein MacA

DDJNKIGN_00004 CDS hypothetical protein

DDJNKIGN_00005 CDS hypothetical protein

DDJNKIGN_00006 CDS hypothetical protein

DDJNKIGN_00007 CDS hypothetical protein

DDJNKIGN_00008 CDS pstA_1 Phosphate transport system permease protein PstA

DDJNKIGN_00009 CDS pstA_2 Phosphate transport system permease protein PstAThis file gives us a list of all the sequences that Prokka has identified as being protein-coding, along with the gene name (if there is one) and the protein product (again, if there is one).

You will notice that some of the output are labelled simply “hypothetical protein”. This means the locus in questions looks like a protein-coding gene, but there isn’t a match for it in any of the databases used by Prokka to label genes.

Others have a gene and product name, meaning Prokka was able to successfully identify them as a specific gene. The product column tells you the name of the protein this gene codes for.

We can then look at the .faa file to see the sequences of these proteins.

Code

head bin.45.faaOutput

>DDJNKIGN_00001 hypothetical protein

MTSSTVINTLVAAQTPILKQNLRPVSVWLHHCGLGGVQASWIQFRDSLRQAIIDALSAAG

MTDCMNELKYRWGL

>DDJNKIGN_00002 hypothetical protein

MQPRPGIPFAGALVPLSTFNKTALRSNSIDLTNPPQLEPFTRREQYRIVVSGDEPDCDDT

LELPVWDCDLIRKCYEVSYHKARLDYYGPAAPFSPKDMTSFRGSSRQCWERTERLRSAGC

TTSRPINCLRQILNVSWTKNMSAVLAGGLLQGLRPEPQLDPAWAAFFALPDIEITSLRST

GTSSPDRTRSRKRTPSAESRRPWRCHGPQPVLPG

>DDJNKIGN_00003 Macrolide export protein MacA

MTSKHIGMVAGAMAFIAAGVGCARSRTAAAGDERPAVSVVKIARGDLSQGLTLAAEFRPFWhat next?

Now we have information about the various genes (and the proteins they code for) present in one of our bins. What can we do with this information?

Relating genes to an online database

There are tools available which allow you to visualise the proteins in your bin and how they fit into different metabolic pathways. Some of these are available through your browser.

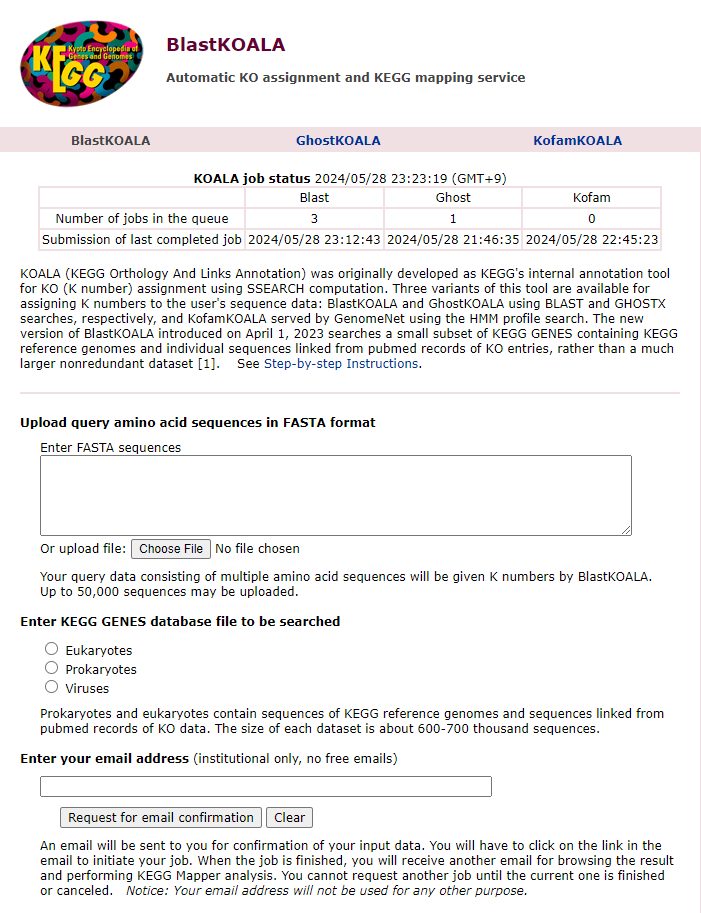

One such tool is BlastKOALA, where you can upload the .faa file we just looked at and get back a breakdown of the proteins mapped to the KEGG database (a database of molecular interaction maps). Start by downloading the .faa file to your local maching using scp:

Code

scp -i login-key-instanceNNN.pem csuser@instanceNNN.cloud-span.aws.york.ac.uk:~/cs_course/results/prokka/bin.45/bin.45.faaYou can then upload this file onto BlastKOALA. BlastKOALA is a tool which can annotate the sequences with K numbers. These then relate back to the KEGG database.

You should click on the “Choose file” button and navigate to where your *.faa file is located on your computer.

Choose the Prokaryotes database as the one to search - you can run it again with eukaryotes and/or viruses if you like later. However, we’re mostly expecting to see prokaryotes so this will be the most useful output.

Once you have pressed submit you should be re-directed to a screen that says “Request accepted”. You will also be sent an email with two links, one to submit the job and one to cancel. Make sure you press the submit link as your job will not be running without it! If you haven’t received an email, check your spam.

Once you have pressed the submit link in the email you should be redirected to a BlastKOALA page that says “Job submitted”. This is an online server shared by lots of people, so your job has to queue with other jobs before it can be executed. This may take a while. You will recieve an email when the job has completed.

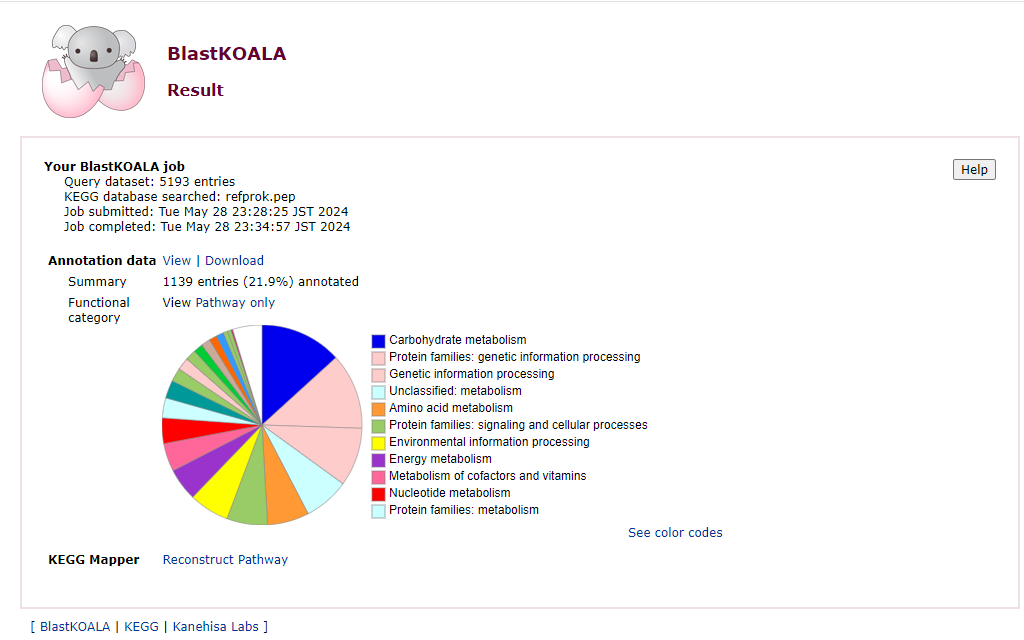

Once the job has been completed you will receive a link by email. From this you can explore the annotated MAG. You can view/download the data and use the KEGG mapper reconstruct pathway option to see how these genes interact with each other.

Using an annotation tool like this can help you understand more about the genes and pathways present in your sample(s). For example, as previously described, the paper this data is pulled from uses functional annotation of MAGs to look for genes associated with denitrification pathways.

Building a tree from the 16S sequence

Prokka is able to identify 16S sequences present in our MAGs. This can be used to build a quick taxonomic tree to see what organisms our MAG is related to.

First we will search for the presence of 16S sequences in the Prokka output.

While still logged into the instance, navigate to the Prokka output directory you generated earlier (~/cs_course/results/prokka/bin.45). Once in that directory we can search for sequenced identified as being 16S in the .tsv file using grep:

Code

grep 16S *.tsvYou should get a result similar to the below. Yours may differ slightly depending on the MAG you ran.

Output

NBEAANKK_00310 CDS yrrK 3.1.-.- Putative pre-16S rRNA nuclease

NBEAANKK_02181 rRNA 16S ribosomal RNAIf you don’t get an output here it may be that your MAG doesn’t have any 16S sequences present. In the case of this lesson, that means you have run Prokka on a less complete MAG than the one we used. You should double check your output from CheckM and pick a MAG that is highly complete to run through Prokka instead.

Our output shows that there is 1 full size 16S ribosomal RNA genes present in our data, and a putative rRNA nuclease (which we can discount as it isn’t an rRNA).

The next step is to pull out the sequence of one of these 16S rRNA genes and run it through a BLAST database. This is possible using the .ffn file which gives the sequences in nucleotide format. We’ll need to search the .ffn file for the tag associated with our gene of interest (the first column in the output above).

We do this using seqkit with a grep option, which you can read more about here). Here’s the format of this command:

Code

seqkit grep -p <prokka_id> <prokka.ffn>So in our case this command would be:

Code

$ seqkit grep -p NBEAANKK_02181 bin.45.ffnYou can see the output of the command below:

Output

>NBEAANKK_02181 16S ribosomal RNA

ACGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAGAGCGAACGCTGGCGGCGTGCTTAACACATGCAAGTCG

AGTGCGCGCCTGTAGCAATACAGGTGGCGCACGGCGCACGGGTGCGTAACACGTGGGTAA

TCTGCCCTTCGATGGGGAATAACTCGCCGAAAGGCGAGCTAATTCCGCATAACATTCCGA

GAACTTTGGTTTTTGGATTCAAAGGCGTAAGTCGTCGGAGGAGGAGCCCGCGCACGATTA

GCTAGTTGGTGAGGTAACGGCTCACCAAGGCTATGATCGTTAGCTGGTCTGAGAGGATGG

CCAGCCACACTGGAACTGAGACACGGTCCAGACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTGGGGAATC

TTGCACAATGGGCGAAAGCCTGATGCAGCGACGCCGCGTGGGGGATGAAGCTTTTCGGAG

TGTAAACCCCTTTCGACCCGGACGAATGCCTCGCAAGAGGACTGACGGTACGGGTATAAG

AAGCCCCGGCTAACTACGTGCCAGCAGCCGCGGTAAGACGTAGGGGGCCAGCGTTGCTCG

GAATTACTGGGTGTAAAGGGTTCGTAGGCGGTGTGGCAAGTCGGGAGTGAAATCTCTGGG

CTCAACCCAGAGGCTGCTTCCGAAACTGCTGTGCTTGAGTGTGGGAGAGGCGCGTGGAAT

TGCAGGTGTAGCGGTGAAATGCGTAGATATCTGCAGGAACACCCGTGGCGAAAGCGGCGC

GCTGGACCACAACTGACGCTGAGGAACGAAAGCTAGGGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGATACCC

TGGTAGTCCTAGCCCTAAACGATCAGGACTTGGGGTGCCGCCCGTTCGGGCGTCGTCCCG

GAGCTAACGCGTTAAGTCCTGCACCTGGGGAGTACGGTCGCAAGACTGAAACTCAAAGGA

ATTGACGGGGGCCCGCACAAGCGGTGGAACATGTGGTTCAATTCGACGCTACGCGAGGAA

CCTTACCTGGGCTCGAAATGCTTATGACCAGCTGTAGAAATACGGCCTTCCCGCAAGGGA

CAGGAGTATAGGCGCTGCATGGCTGTCGTCAGCTCGTGCCGTGAGGTGTTGGGTTAAGTC

CCGCAACGAGCGCAACCCCTGCACGTAGTTGCCACTCCGCAAGGAGGGAACTCTACGTGG

ACTGCTCCGGATAACGGAGAGGAAGGTGGGGATGACGTCAAGTCCGCATGGCCTTTATGT

CCAGGGCTACACACGTGTTACAATGCAGGGTACAAACCGTTGCCAACCCGCGAGGGGGAG

CTAATCGGAAAAAACTCTGCTCAGTTCGGATTGCAGTCTGCAACTCGACTGCATGAAGCC

GGAATCGCTAGTAATGGCGTATCAGATCGACGCCGTGAATACGTTCCCGGGCCTTGTACA

CACCGCCCGTCACATCACGAAAGTGAGTTGTACTAGAAGTCGTCACGCTGACCGCAAGGA

GGCAGACGCCCAAGGTATGACCCATGATTGGGGTGAAGTCGTAACAAGGTAGCCGTAGGA

GAACCTGCGGCTGGATCACCTCCTTTNow we have the 16S rRNA sequence we can upload this to BLAST and search the 16S database to see what organisms this MAG relates to.

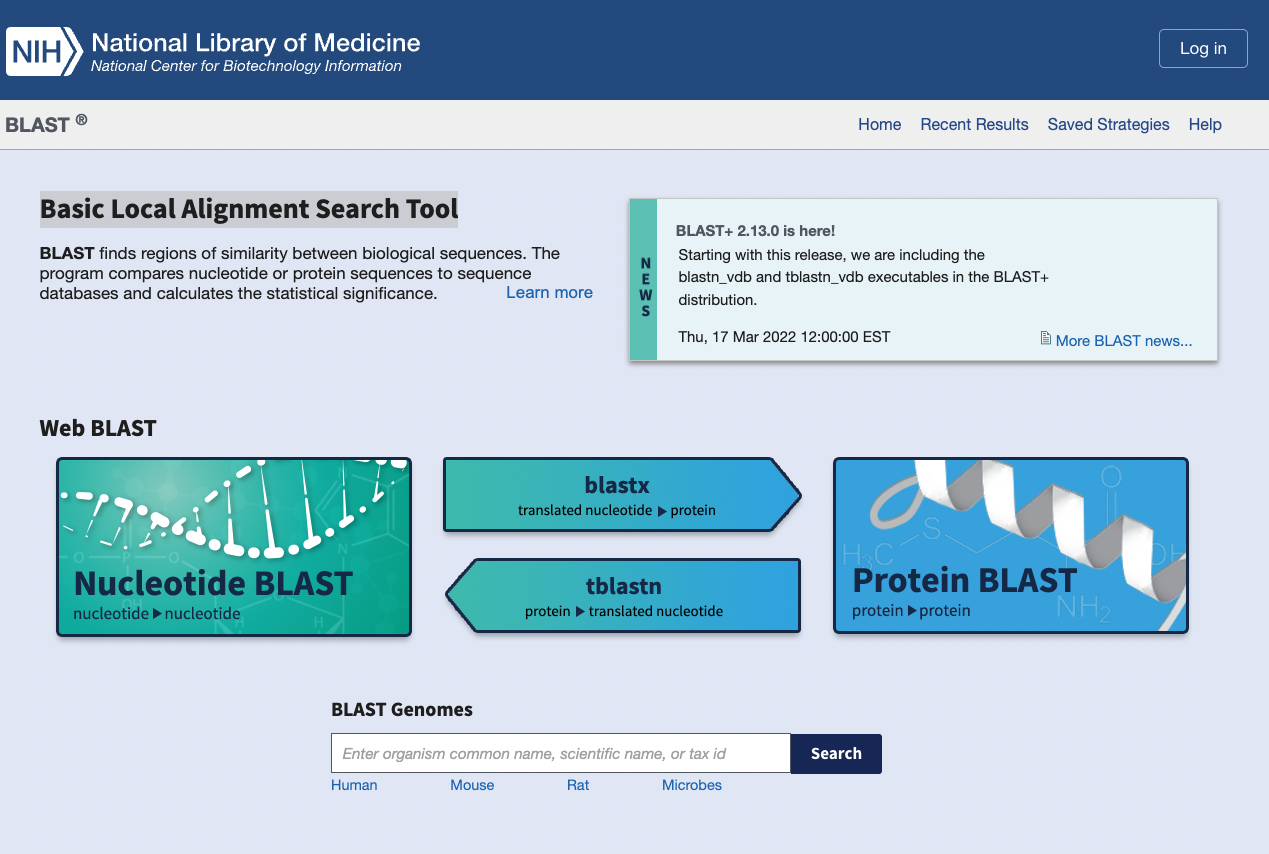

BLAST

We will be using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) which is an algorithm to find regions of similarity between biological sequences. BLAST is a very popular program in bioinformatics so you may be familiar with the online BLAST server run by NCBI.

We will be using the online server, available at BLAST.

Select the button that says “Nucleotide BLAST”.

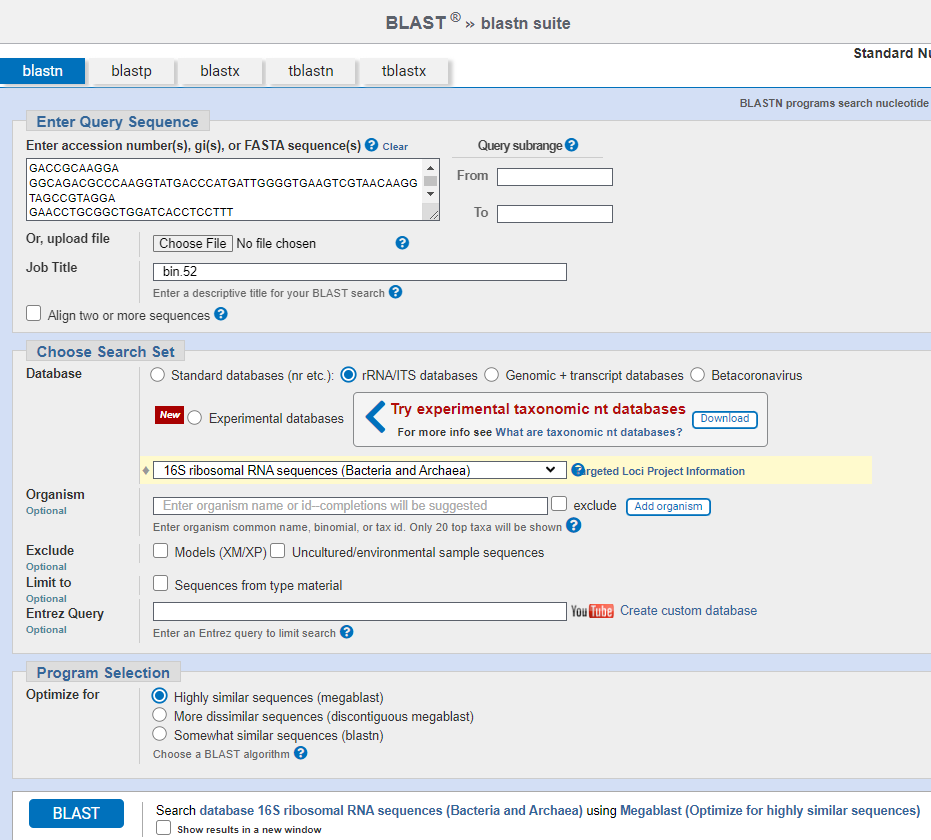

Under “Choose Search Set” set the database to “rRNA/ITS database”. Then, copy and paste the 16S sequence from your instance into the box at the top titled “Enter accession number(s), gi(s), or FASTA sequence(s)”

Your screen should look something like the below:

Now, click the blue BLAST button!

Your job will then be added to a queue of other jobs until there is space for it to run. Usually this is only a couple of minutes, especially as the sequence length and database size we are using are small. Make sure you leave the tab open while you wait so you can see your results when they arrive.

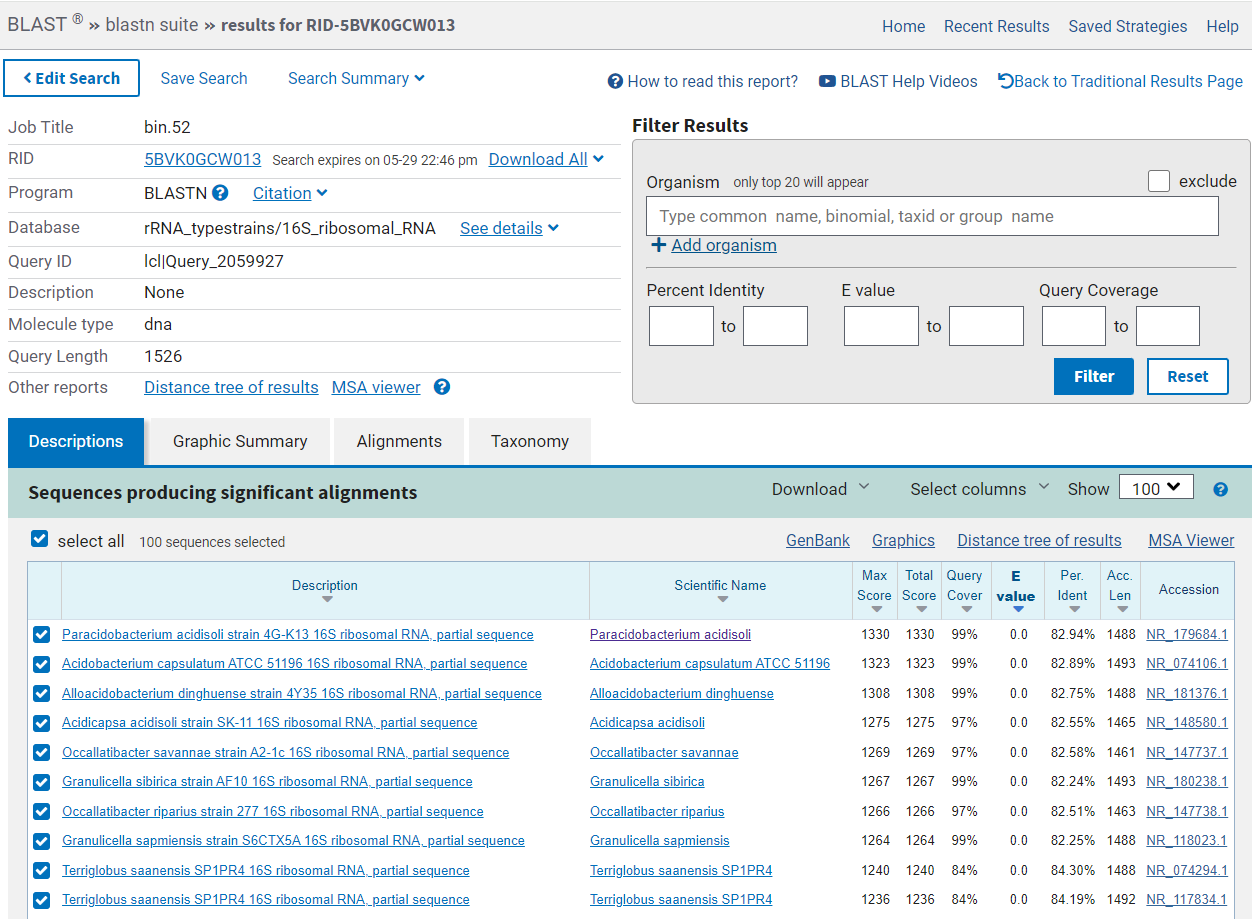

Your ouput should look like this:

From here you can explore the sequences that were aligned to your 16S sequence using the “Descriptions”, “Graphic Summary”, “Alignments” and “Taxonomy” tabs. You can also browse the “Distance tree of results” to see where your 16S sequence lies in relation to other species.

You will now have a 16S sequence from the MAG that you have chosen. Use the output from your BLAST search to answer these questions.

- What do you think is the most likely annotation for your MAG? ?

- Which columns in the BLAST output do you think are the most important for selecting which is the best hit?

- Now you have identified this MAG, try repeating the process for the other bins and see which organisms they belong to. Which are the best hits for these MAGs?

- This will vary depending on the MAG you have picked but it will be one of the first hits in the output. The “closest” match will probably be the one with the highest total score. However these are not the only columns worth using to identify the best hit.

- Other columns worth looking at (because the top hit may not be the best) are the query cover, percent identity and the E-value.

- percent identity is how similar the query sequence (your input) is to the target AKA how many characters are identical. Higher percent identity = more similar sequences

- query coverage is the percentage of the query sequence that overlaps the target. If there is only a small overlap then the match is less significant, even if it has a very high percent identity. We want as much of the two sequences to be identical as possible.

- E-value is the number of matches you would expect to see by chance. This is dependent on the size of the database. Lower E-value = less likely to be by chance = a better match.