Redirection

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How can I search within files?

How can I combine existing commands to do new things?

Objectives

Employ the

grepcommand to search for information within files.Print the results of a command to a file.

Construct command pipelines with two or more stages.

Searching files

We discussed in a previous episode how to search within a file using less. We can also

search within files without even opening them, using grep. grep is a command-line

utility for searching plain-text files for lines matching a specific set of

characters (sometimes called a string) or a particular pattern

(which can be specified using something called regular expressions). We’re not going to work with

regular expressions in this lesson, and are instead going to specify the strings

we are searching for.

Let’s give it a try!

Nucleotide abbreviations

The four nucleotides that appear in DNA are abbreviated

A,C,TandG. Unknown nucleotides are represented with the letterN. AnNappearing in a sequencing file represents a position where the sequencing machine was not able to confidently determine the nucleotide in that position. You can think of anNas being aNy nucleotide at that position in the DNA sequence.

We’ll search for strings inside of our fastq files. Let’s first make sure we are in the correct directory:

$ cd ~/cs_course/data/illumina_fastq

However, suppose we want to see how many reads in our file have bad segments containing three or more unclassified nucleotides (N) in a row.

Determining quality

In this lesson, we’re going to be manually searching for strings of bases within our sequence results to illustrate some principles of file searching. It can be really useful to do this type of searching to get a feel for the quality of your sequencing results, however, in your research you will most likely use a bioinformatics tool that has a built-in program for filtering out low-quality reads. You’ll learn how to use one such tool in a later lesson.

To search files we use a new command called grep. The name “grep” comes from an abbreviation of global regular expression print.

Let’s search for the string NNN in the ERR4998593_1 file:

$ grep NNN ERR4998593_1.fastq

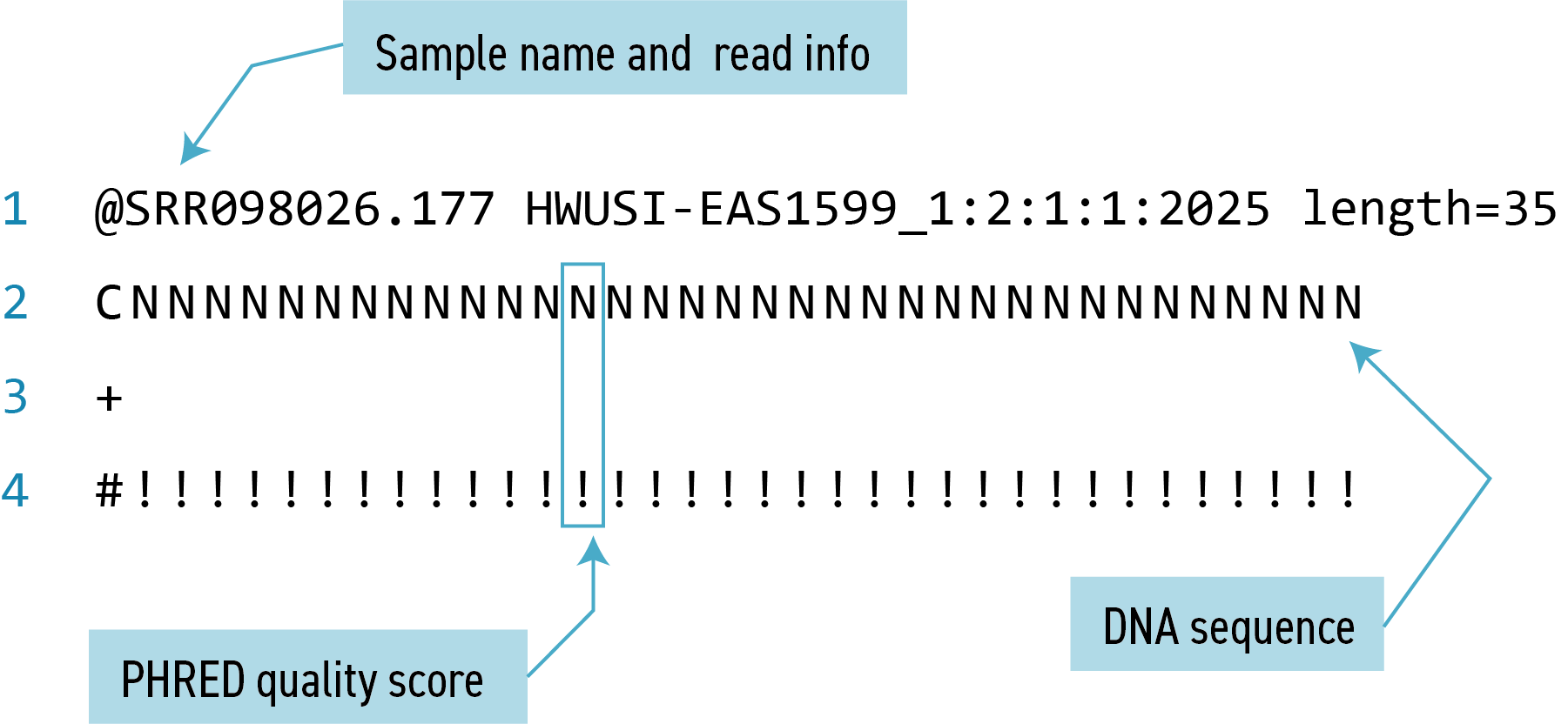

This command returns quite a lot of output to the terminal. Every single line in the ERR4998593_1 file that contains at least 3 consecutive Ns is printed to the terminal, regardless of how long or short the file is. We may be interested not only in the actual sequence which contains this string, but in the name (or identifier) of that sequence. Think back to the FASTQ format we discussed previously - if you need a reminder, you can click to reveal one below.

Hint

To get all of the information about each read, we will return the line immediately before each match and the two lines immediately after each match.

We can use the -B argument for grep to return a specific number of lines before each match. The -A argument returns a specific number of lines after each matching line. Here we want the line before and the two lines after each matching line, so we add -B1 -A2 to our grep command:

$ grep -B1 -A2 NNN ERR4998593_1.fastq

One of the sets of lines returned by this command is:

@ERR4998593.50651366 50651366 length=151

TCCTTGCGGAGCCGGGCATGCAGGNCCTGCAGGTAGNGGCGGCGGCAGGNGCCGCCGCCGTCTACCACGGTGTANCGNNCNANNNNNCANTCATCGACGGNNGGTGNGACNNCTGCGATCTTGCGNCGCCTGGTCTNGCGGCCATCCTCTN

+

FFF,FFFFFFFF:,,F:F,FFFFF#,:F,FFFF:F,#,FFFFF::FF:,#FFFFFFFFF:F,FF,FFFF,F,FF#,F##:#:#####:F#FFFFFFF,FF##:FFF#F:F##FFF,FFFFFF,,,#FF:F:,FFFF#F:::F:FFF:FF,#

Exercise

Search for the sequence

AAAACCCCGGGGTTTTin theERR4998593_1.fastqfile. Have your search return all matching lines and the name (or identifier) for each sequence that contains a match. What is the output?Search for the sequence

AACCGGTTAACCGGTTin both FASTQ files. Have your search return all matching lines and the name (or identifier) for each sequence that contains a match. How many matching sequences do you get? (this may take up to 4 minutes to complete so be patient!)Solution

grep -B1 AAAACCCCGGGGTTTT ERR4998593_1.fastq@ERR4998593.49988640 49988640 length=151 GGTCCATGAAGCTTGTACTGCGCGCCGATATTCTCGAAGCCGAGGCCCTAGTCCGCAAAAAACAAAAACCCCGGGGTTTTGGCCCCGGGGTTTGTCGTTTGAGCGTTTGCCGCGGCGATCAGAACCGGTAGTTGACGCCGGCGCGAACGAT -- @ERR4998593.16888007 16888007 length=151 GCCGAGGCCCTAGTCCGCAAAAAACAAAAACCCCGGGGTTTTGGCCCCGGGGTTTGTCGTTTTAGCGTTTGCCGCGGCGATCAGAACCGGTAGTTGACGCCGGCGCGAACGATGTTGGTGGTGAACGACACGTTGTCGGTCACGAACGGTC -- @ERR4998593.39668571 39668571 length=151 CCCCGGGGCCAAAACCCCGGGGTTTTTGTTTTTTGCGGACTAGGCCTCGGCTTCGAGAATATCGGCGCGCAGTCCAAGCTTCATGGACCTGTCGTGACCCAAGATGGCGGATCAGGCGGGAGACTCAGGTTTTCCCGAAAGGTCTTTATGC

grep -B1 AACCGGTTAACCGGTT *.fastqERR4998593_1.fastq-@ERR4998593.64616570 64616570 length=151 ERR4998593_1.fastq:GACAAGCTCATCTTCCAAAATCCGCAACGGTTTTTAAGCCAGTGCCCGAAATTTAGATTAACCGATTAACCGGTTAACCGGTTCGTAGGAGACGGGTAACGAGACTCTAACTCAAGTTTCGCATACTACCACCAAAACAGCCCGTCCGCGT -- ERR4998593_1.fastq-@ERR4998593.64617528 64617528 length=151 ERR4998593_1.fastq:GACAAGCTCATCTTCCAAAATCCGCAACGGTTTTTAAGCCAGTGCCCGAAATTTAGATTAACCGATTAACCGGTTAACCGGTTCGTAGGAGACGGGTAACGAGACTCTAACTCAAGTTTCGCATACTACCACCAAAACAGCCCGTCCGCGT -- ERR4998593_1.fastq-@ERR4998593.52741374 52741374 length=151 ERR4998593_1.fastq:GACAAGCTCATCTTCCAAAATCCGCAACGGTTTTTAAGCCAGTGCCCGAAATTTAGATTAACCGATTAACCGGTTAACCGGTTCGTAGGAGACGGGTAACGAGACTCTAACTCAAGTTTCGCATACTACCACCAAAACAGCCCGTCCGCGT -- ERR4998593_2.fastq-@ERR4998593.2096117 2096117 length=151 ERR4998593_2.fastq:ATTGGCTGGCGGCAGTCGCGTTGGCGGCTTGGCGGTTAACCGGTTAACCGGTTGACTAATGGGAGGATAACACTTCGCGACAGGAACGCAACACAATTCCGGATCAATAGGGCAACTGCCCTGGGATGGTTTTTGAGGTGGACACGGACCA -- ERR4998593_2.fastq-@ERR4998593.11478972 11478972 length=151 ERR4998593_2.fastq:GAACAGGGCTGTTAGTTAACCGGTCAAAGCCGCCTTAACCGGTTAACCGGTTGTAACGCCCCGCTATGCTCGTTGTGTCCGCTATCTCTGTGATTGTGTTTGTTTCGGTGTTTGCTTCGGTTTGCCGTTTGTCTATGCCGAGAAGTGGAGG

Redirecting output

grep allowed us to identify sequences in our FASTQ files that match a particular pattern.

All of these sequences were printed to our terminal screen, but in order to work with these sequences and perform other operations on them, we will need to capture that output in some way.

We can do this with something called “redirection”. The idea is that we are taking what would ordinarily be printed to the terminal screen and redirecting it to another location. In our case, we want to print this information to a file so that we can look at it later and use other commands to analyse this data.

Redirecting output to a file — the > command

The command for redirecting output to a file is >.

Let’s try out this command and copy all the records (including all four lines of each record) in our FASTQ files that contain ‘NNN’ to another file called bad_reads.txt. The new flag --no-group-separator stops grep from putting a dashed line (–) between matches. The reason this is necessary will become apparent shortly.

$ grep -B1 -A2 NNN --no-group-separator ERR4998593_1.fastq > bad_reads.txt

The prompt should sit there a little bit, and then it should look like nothing

happened. But type ls. You should see a new file called bad_reads.txt.

File extensions

You might be confused about why we’re naming our output file with a

.txtextension. After all, it will be holding FASTQ formatted data that we’re extracting from our FASTQ files. Won’t it also be a FASTQ file? The answer is, yes - it will be a FASTQ file and it would make sense to name it with a.fastqextension. However, using an extension such as.txtmakes it easy to distinguish the files you may generate through some exploratory processing, as the one we just made with thegrepprogram, from the original sequencing files of your project. So you can easily select all the files with a specific extension for further processing using the wildcard*character, for example:grep .. *.fastqormv *.txt newlocation.

Counting number of lines in files — the wc program

We can check the number of lines in our new file using a command called wc. wc stands for word count. This command counts the number of words, lines, and characters in a file. The FASTQ file may change over time, so given the potential for updates, make sure the output of your wc command below matches your instructor’s output.

As of February 2023, wc gives the following output:

$ wc bad_reads.txt

52 78 4511 bad_reads.txt

This will tell us the number of lines, words and characters in the file. If we want only the number of lines, we can use the -l flag for lines.

$ wc -l bad_reads.txt

52 bad_reads.txt

The --no-group-separator flag used above prevents grep from adding unnecessary extra lines to the file which would alter the number of lines present.

Exercise

Try these questions on your own first. Then, if you are attending an instructor-led workshop, discuss your answers in your breakout room. Nominate someone from your group to feed back on the forum.

- How many sequences are there in

ERR4998593_1.fastq? Remember that every sequence is formed by four lines.- How many sequences in

ERR4998593_1.fastqcontain at least 5 consecutive Ns?Solution

1.

$ wc -l ERR4998593_1.fastq137054440 ERR4998593_1.fastqNow you can divide this number by four to get the number of sequences in your fastq file (34263610).

2.

$ grep NNNNN ERR4998593_1.fastq > bad_reads.txt $ wc -l bad_reads.txt3 bad_reads.txt

The command > redirects and overwrites

We might want to search multiple FASTQ files for sequences that match our search pattern.

However, we need to be careful, because each time we use the > command to redirect output

to a file, the new output will replace the output that was already present in the file.

This is called “overwriting” and, just like you don’t want to overwrite your video recording

of your kid’s first birthday party, you also want to avoid overwriting your data files.

$ grep -B1 -A2 NNN --no-group-separator ERR4998593_1.fastq > bad_reads.txt

$ wc -l bad_reads.txt

52 bad_reads.txt

$ grep -B1 -A2 NNNNNNNNNN --no-group-separator ERR4998593_1.fastq > bad_reads.txt

$ wc -l bad_reads.txt

0 bad_reads.txt

Here, the output of our second call to wc shows that we no longer have any lines in our bad_reads.txt file. This is because the second string we searched (NNNNNNNNNN) does not match any strings in the file. So our file was overwritten and is now empty.

The command >> redirects and appends

We can avoid overwriting our files by using the command >>. >> is known as the “append redirect” and will append new output to the end of a file, rather than overwriting it.

$ grep -B1 -A2 NNN --no-group-separator ERR4998593_1.fastq > bad_reads.txt

$ wc -l bad_reads.txt

52 bad_reads.txt

$ grep -B1 -A2 NNNNNNNNNN --no-group-separator ERR4998593_1.fastq >> bad_reads.txt

$ wc -l bad_reads.txt

52 bad_reads.txt

The output of our second call to wc shows that we have not overwritten our original data.

Redirecting output as input to other program — the pipe | command

Since we might have multiple different criteria we want to search for, creating a new output file each time has the potential to clutter up our workspace.

We also thus far haven’t been interested in the actual contents of those files, only in the number of reads that we’ve found. We created the files to store the reads and then counted the lines in the file to see how many reads matched our criteria.

There’s a way to do this, however, that doesn’t require us to create these intermediate files - the pipe command (|).

This is probably not a key on your keyboard you use very much, so let’s all take a minute to find that key. For the standard QWERTY keyboard

layout, the | character can be found using the key combination

- Shift+\

What | does is take the output that is scrolling by on the terminal and uses that output as input to another command.

When our output was scrolling by, we might have wished we could slow it down and

look at it, like we can with less. Well it turns out that we can! We can redirect our output

from our grep call through the less command.

$ grep -B1 -A2 NNN ERR4998593_1.fastq | less

We can now see the output from our grep call within the less interface. We can use the up and down arrows

to scroll through the output and use q to exit less.

If we don’t want to create a file before counting lines of output from our grep search, we could directly pipe

the output of the grep search to the command wc -l. This can be helpful for investigating your output if you are not sure

you would like to save it to a file.

$ grep -B1 -A2 NNN --no-group-separator ERR4998593_1.fastq | wc -l

52

Custom

grepcontrolUse

man grepto read more about other options to customize the output ofgrepincluding extended options, anchoring characters, and much more.

Redirecting output is often not intuitive, and can take some time to get used to. Once you’re comfortable with redirection, however, you’ll be able to combine any number of commands to do all sorts of exciting things with your data!

We’ll be using the redirect > and pipe | later in the course as part of our analysis workflow, so you will get lots of practice using them.

None of the command line programs we’ve been learning do anything all that impressive on their own, but when you start chaining them together, you can do some really powerful things very efficiently.

Key Points

grepis a powerful search tool with many options for customization.

>,>>, and|are different ways of redirecting output.

command > fileredirects a command’s output to a file.

command >> fileredirects a command’s output to a file without overwriting the existing contents of the file.

command_1 | command_2redirects the output of the first command as input to the second command.